Figure 1

Building America research has provided essential guidance for one of the most challenging construction assemblies in cold-climate high-performance homes. Basements can easily develop mold, rot, and odor problems if not designed properly. Building America researchers have investigated basement insulation systems that keep the space dry, healthy, and odor-free. These systems effectively address the complexity of heat and moisture movement through basement walls.

The moisture that can contribute to potential mold and rot problems in basements can come from both inside and outside the house. Interior air carries vapor that will condense on the basement walls and floor if those surfaces are below the dew point temperature. When cellulose or fiberglass insulation is installed in contact with basement walls, it can absorb large amounts of moisture and stay chronically damp.

The problem is compounded when an impermeable vapor barrier such as plastic is used on the interior because it will trap moisture in the wall. Through extensive field tests and analysis, Building America researchers have developed insulation strategies that can keep a basement dry and warm.

Two factors are key: choosing the right insulation and installing it the right way.

Insulation on the interior of basement walls must be installed in an airtight manner that keeps airborne vapor from condensing on cold walls. At the same time, the material must be a vapor retarder that is semi-permeable so any moisture coming through the wall can dry to the interior. (See figure 1).

- Cold concrete foundation wall must be protected from interior moisture-laden air in summer and winter

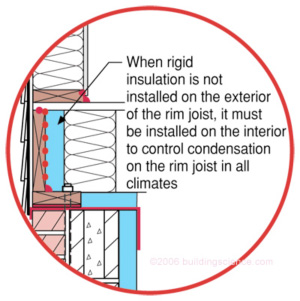

- Rim joist assembly must be insulated with air impermeable insulation or insulated on the exterior

- Rigid insulation completely wraps exposed concrete preventing interior air from contacting potential concrete condensing surface

- Seams in rigid insulation and joints to other materials sealed to provide air barrier

- Rigid insulation is vapor semi-impermeable or vapor semi-permeable (foil facing or plastic facing not present)

- Rigid insulation provides bond break between foundation wall and slab when insulation is installed before slab is poured

Figure 2a

Figure 2b

Three types of rigid foam can be used to insulate the interior of basement walls: XPS, EPS (expanded polystyrene), and polyisocyanurate. For moisture control, the foam panels must adhere completely to the foundation wall, with no air gaps behind them. Edges and seams must be tightly sealed with Tyvek tape or a similar product. When finishing the wall, leave at least a ½-inch gap between the drywall and the floor. Building America’s recommendations make it possible to insulate basements with little risk of moisture problems, and the insulation will reduce your energy bills. The savings depends on climate, fuel cost, the type of heating system, and the occupants’ lifestyle. The savings can be significant, since 10% to 30% of a home’s total heat loss occurs through the basement.

Key Lessons Learned

- Air sealing is a crucial defense against condensation. The rim joists must be air sealed and insulated. (See figures 2a,2b) • Fiberglass batt or cellulose insulation should not be in contact with foundation walls.

- Do not install polyethylene sheeting, vinyl or foil wallpaper, or epoxy, oil, or alkyd paint on the interior of basement walls. These are Class I vapor retarders and will trap moisture in the walls.

- Do not insulate a basement ceiling unless the home is in a dry climate and the basement will not be used as living space.

Walls

Figure 3

Basement walls should be insulated with non-water sensitive insulation, up to two inches of unfaced extruded polystyrene (R-10) that prevents interior air from contacting cold basement surfaces— the concrete structural elements and the rim joist framing. Allowing interior air (that is usually full of moisture, especially in the humid summer months) to touch cold surfaces will cause condensation and wetting, rather than the desired drying. The structural elements of below grade walls are cold (concrete is in direct contact with the ground)—especially when insulated on the interior. Of particular concern are rim joist areas—which are cold not only during the summer but also during the winter. This is why it is important that interior insulation assemblies be constructed as airtight as possible. (See figure 3)

Figure 4 (Incorrect Way)

The best insulations to use are foam based and should allow the foundation wall assembly to dry inwards. The foam insulation layer should generally be vapor semi impermeable (greater than 0.1 perm), vapor semi permeable (greater than 1.0 perm) or vapor permeable (greater than 10 perm) (Lstiburek, 2004). The greater the permeance the greater the inward drying and therefore the lower the risk of excessive moisture accumulation. In most basement wall situations, the foam plastic insulation material will need to be covered by a fire/ignition barrier. ½” gypsum board usually provides sufficient ignition barrier (check your local building code). When this ignition barrier is supported on a stud wall, the cavities of this wall may be filled with supplemental insulation. It is important that the airtight foam insulation assembly be continuous behind the framed wall. No interior vapor barriers(plastic OR paper faced batt) should be installed in order to permit inward drying (See figure 4).